Joseph Spence

Joseph Spence (1910-1984) was a virtuosic Bahamian guitarist whose mastery of his instrument continues to capture the musical imaginations of artists across the globe. His records, assembled by an enthusiastic set of the Northeast folk revival’s most respected producers, drew upon his country’s cache of folk traditions to reimagine everything from calypso to pop to gospel. Throughout the ‘60s and ‘70s, and beyond, disciples such as Richard Thompson, Catfish Keith, and the Grateful Dead turned to Spence’s records for inspiration. They were awed by his ability to temper intricate layers of improvisation with a breezy sense of wonder, a wholly individual sound that left an indelible mark on the history of guitar music.

Spence was born in the Small Hope settlement on Andros, the largest island in the Bahamas. Due to a wide expanse of shallow water that renders much of its coastline treacherous, Andros remained relatively isolated for much of the 20th century, allowing its musical traditions to thrive with minimal influence from the outside world. By the time he was 14, Spence was playing guitar for local dances with his uncle’s band. As a young man, he sought economic opportunity in the national capital Nassau, where he lived for the rest of his life (excluding a two-year stint as a migrant farmhand in the American South, which familiarized him with the blues). Though he did not make his living as a musician, Spence brought music into his work, harmonizing with fellow sponge fishermen on expeditions or accompanying local singers on the docks. Word spread around both Nassau and Andros, and he became a well-respected musician in his community, known as a superlative talent among neighbors and friends.

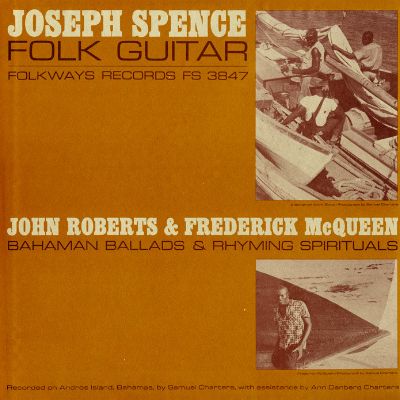

His renown was purely local, however, until he met American researchers Sam Charters and Ann Danberg while he was visiting old friends on Andros in 1958. The soon-to-be-married couple was inspired to travel to the Bahamas by Alan Lomax’s recordings from a 1935 trip with Mary Elizabeth Barnicle. Lomax’s liner notes pointed to Andros as a prime locale for traditional Bahamian music. It was there that the pair found Spence, sitting on a pile of bricks and playing his guitar to pass the time. Charters was so convinced that a second guitarist was playing that he went in search of one behind a nearby wall. Later that day, Charters and Danberg recorded Spence on a back porch, since his eager audience was too big to fit inside. They persuaded Moses Asch to release the recording as a 10-inch LP through Folkways, the first of many entries in Spence’s long discography.

Spence’s music was unlike anything his international listeners had ever heard. While blues giants like Charley Patton and Robert Johnson played two guitar parts at once, a melody and a bassline, Spence added the instrument’s middle strings to the mix — and improvised rhythmic and melodic variations for all three parts simultaneously, keeping time with his foot. Amidst it all, his voice loosely outlined the original song for reference, mixing lyric fragments with growls, mumbles, and scat syllables. This extraordinarily difficult technique was Spence’s instrumental adaptation of the Bahamian rhyming tradition, a vocal music practice among sponge fisherman in which a lead “rhymer” improvises syncopated verses over the accompaniment sung by a bass and a tenor. It also built from the improvisations of 1930s jazz, the counterpoint of Appalachian shape-note hymnals, the rhythms of centuries-old African music, and a rich collage of other influences. Sometimes, his on-the-spot variations were so exciting that Spence himself would stop playing to join the audience’s astonished uproar.

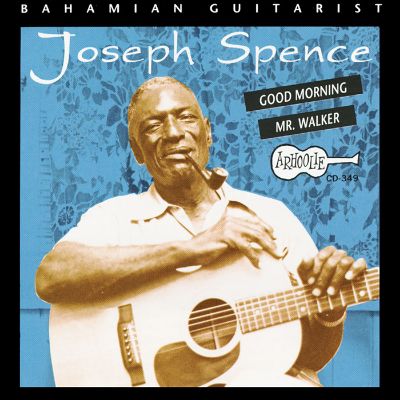

During the ‘60s and ‘70s, Spence became a coveted act for American record producers and festival organizers, often performing alongside his sister and fellow Bahamian Edith Pinder. In addition to his work with Folkways, Spence recorded with Elektra, Nonesuch, Rounder, and Arhoolie Records. Pete Seeger became such an invested fan that he traveled to Nassau to recruit him for a concert. The following year, Spence appeared at the Newport Folk Festival. Between recording sessions and performances, he explored tourist attractions, made friends, and flew kites, unabashedly delighted by the adventure of it all.

Still, nothing could keep Spence away from his Bahamian home for long. He lived out his days in Louise Cottage, the hand-built home he named for his wife, with a snow globe containing the Empire State Building perched atop the mantle. Admiring acoustic guitarists including Ry Cooder and Taj Mahal made pilgrimages to learn from him. Up until his death in 1984, he generously shared his gifts with anyone and everyone in his community, from aspiring musicians to children at the school where he worked as a night watchman. “The voice from heaven,” as the words emblazoned on his guitar amp dubbed Spence, had a universally acknowledged heart of gold.

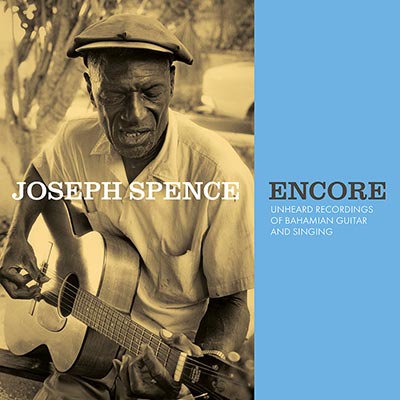

In 2021, Folkways announced the July 16 release of Encore: Unheard Recordings of Bahamian Guitar and Singing, an exuberant collection of never-before-heard recordings of Spence created by Peter K. Siegel in 1965. The album is preceded by the lead single “Run Come See Jerusalem,” Spence’s take on the well-loved folk song describing a 1929 Bahamian shipwreck. His performance is rendered poignantly personal by his own memories of the wreck, during which he helped to pull bodies from the water. The album’s track list also includes two entirely new songs and new performances of old favorites. More than half a century after Charters and Danberg’s first recordings, Encore offers listeners a rare glimpse at Spence’s joyful genius in its prime.