A Tribute to Pete Seeger (1919-2014)

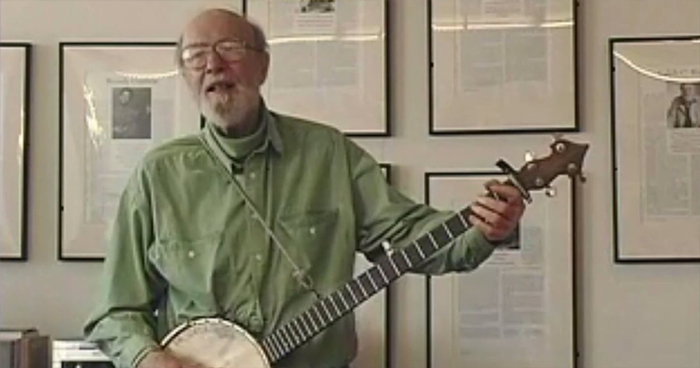

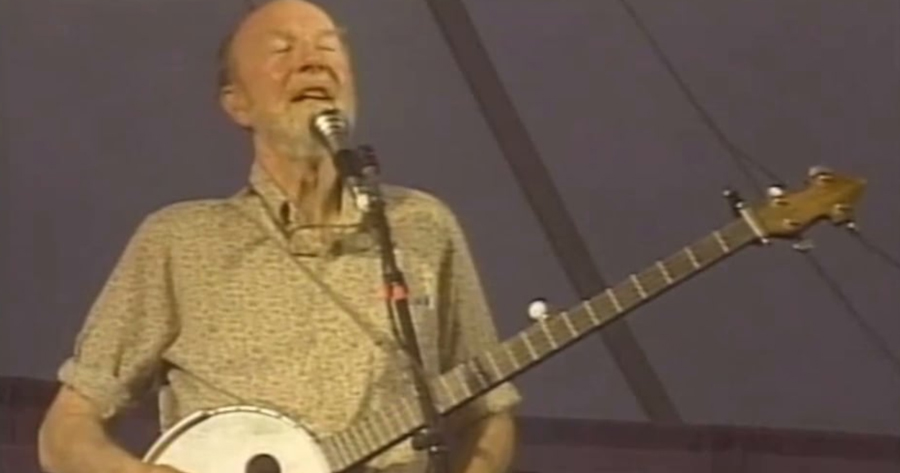

Pete Seeger was a giant of our time. Growing up in a musical family, he had a long and productive career as a folk song leader and social activist. His father was the musicologist Charles Seeger, and his mother Constance was a classical violinist. At one point during his youth, Seeger and his brothers traveled extensively with their parents, entertaining communities throughout the countryside. When he was sixteen, he accompanied his father to Bascom Lamar Lunsford’s folk festival in Asheville, North Carolina. It is there that he first encountered the banjo and fell in love with it.

He went to Harvard hoping to become a journalist, but did not find what he was looking for there. In 1938, he settled in New York City and eventually met Alan Lomax, Woody Guthrie, Aunt Molly Jackson, Lead Belly, and others. The quality of music coming from this group immediately captured his attention. He assisted Alan Lomax at the Library of Congress’ Archive of Folk Song and was exposed to a wonderful array of traditional American music. Many in this group of musicians eventually formed the Almanac Singers in 1940. In addition to Pete, the group included Lee Hays, Woody Guthrie, Bess Lomax, Sis Cunningham, Mill Lampell, Arthur Stern, and others. They lived in a communal home, “The Almanac House,” in New York. The group performed for gatherings, picket lines, and any place where they could lend their voices in support of the social causes they believed in. Later, after World War II, many of the same people became involved in the musical organizations People’s Songs and People’s Artists.

In 1943, Seeger recorded in New York during a production of Earl Robinson’s Lonesome Train. While recording, he stopped by Moses Asch’s little studio and recorded several Spanish Civil War songs for his first acetate discs on Moses Asch’s record label. This was the beginning of a very long and prolific relationship between the two men.

In 1949, Pete Seeger began to perform with three other musicians: his old partner Lee Hays, who had a booming bass voice, Fred Hellerman on guitar and vocals, and Ronnie Gilbert, a young woman with a soaring voice. They called themselves The Weavers and played lovely arrangements of American folk songs, many written by old friends such as Lead Belly and Woody Guthrie. Some of their more popular songs were “Michael Row the Boat Ashore,” “It Takes a Worried Man,” “Wimoweh,” and “Kisses Sweeter Than Wine.” But none were more popular than the double sided 78 rpm hit “Goodnight Irene,” which was learned from Lead Belly, and Hebrew folk song “Tzena Tzena Tzena.” These tunes reached number one and number two, respectively, on the hit parade in 1950.

Later that same year, the book Red Channels appeared. In the anti-Communist hysteria that followed World War II, Red Channels accused well-known Americans, mostly from the arts, entertainment, and journalism fields, of being communists. Seeger’s name appeared in the book and very soon afterward The Weavers’ television program was cancelled, as were many of their performances. Thus began a seventeen year period where Pete Seeger was forced to operate as a blacklisted musician. As late as 1967, when the blacklist had mostly faded, Seeger still had difficulty getting on network television.

Many of the members of the New York folk music scene were suspected of harboring communist sympathies. Pete watched as one-by-one his friends and colleagues were called before the House Un-American Activities Committee. Membership in groups like People’s Songs was bound to get you subpoenaed. Finally, on August 14, 1955, it was Pete’s turn. When queried by the committee, he refused to answer any questions about his political beliefs, stating that “these are very improper questions for any American to be asked" (Dunaway: 213). His uncooperative testimony made it likely that he would be charged with numerous counts of contempt of Congress. This eventually transpired in July 1956, and was followed by an indictment in 1957. The trial came much later, hanging over Seeger’s head for the rest of the decade. The blacklist would haunt the members of the group throughout the 1950s and part of the 1960s.

Video: Pete Seeger recites a poem on the American Flag

Unable to ply his trade in the most lucrative locations and travel without scrutiny, Seeger’s music went underground. This became a period of explosive energy and creativity. Biographer David King Dunaway notes that from 1954 to 1958, Seeger released six LPs per year (Dunaway: 218). During the blacklist, Seeger supported his family by constant traveling, playing small venues, releasing numerous albums, producing documentary films, and authoring a fairly popular book on how to play the 5-string banjo.

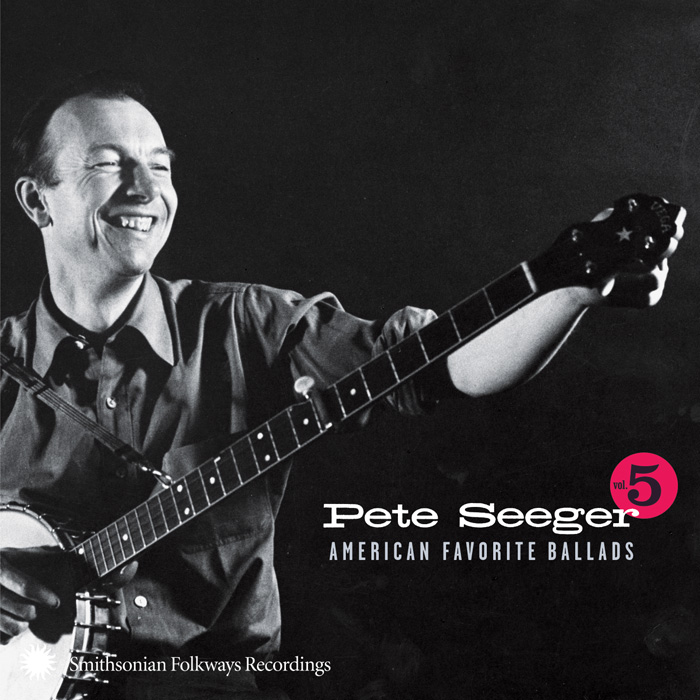

Moses Asch, who in 1948 had started his Folkways label, was an old friend and supporter. He couldn’t have cared less about the blacklist. During the 50s and 60s, Folkways published dozens of Pete’s records. While the blacklisters were worried about Seeger singing before Middle America on the television, radio, or in nightclubs, his children’s records were entertaining a new generation of youngsters in schools and summer camps, where he was also known to make appearances. His great children’s albums from this period remain best sellers today, including his own story Abiyoyo. His series American Favorite Ballads taught a whole generation of young Americans the great American folk songs that Seeger himself had learned.

Many of the young people who heard Seeger in the 1950s became the leaders of the “folk song revival” which began later that decade. Musicians like the Kingston Trio’s Dave Guard were inspired to take up music. It is unfortunate that as the “folk revival” peaked and young groups were landing lucrative record contracts, the man who started them out was blacklisted. During this time, the major music businesses took full advantage of the blacklist by cashing in on appropriation. There was even a network television show called “Hootenanny" that would not allow Seeger to perform—the very man who, along with Woody Guthrie, had introduced the public to the word “hootenanny.”

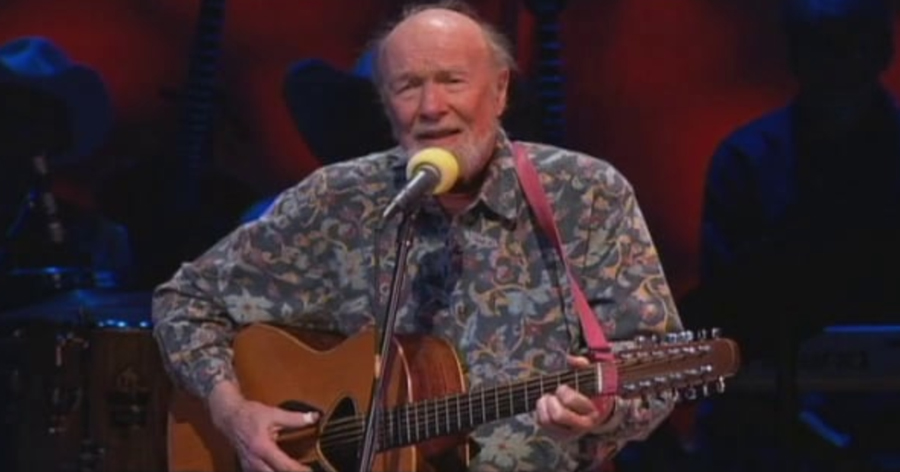

Video: Pete Seeger live performance and interview

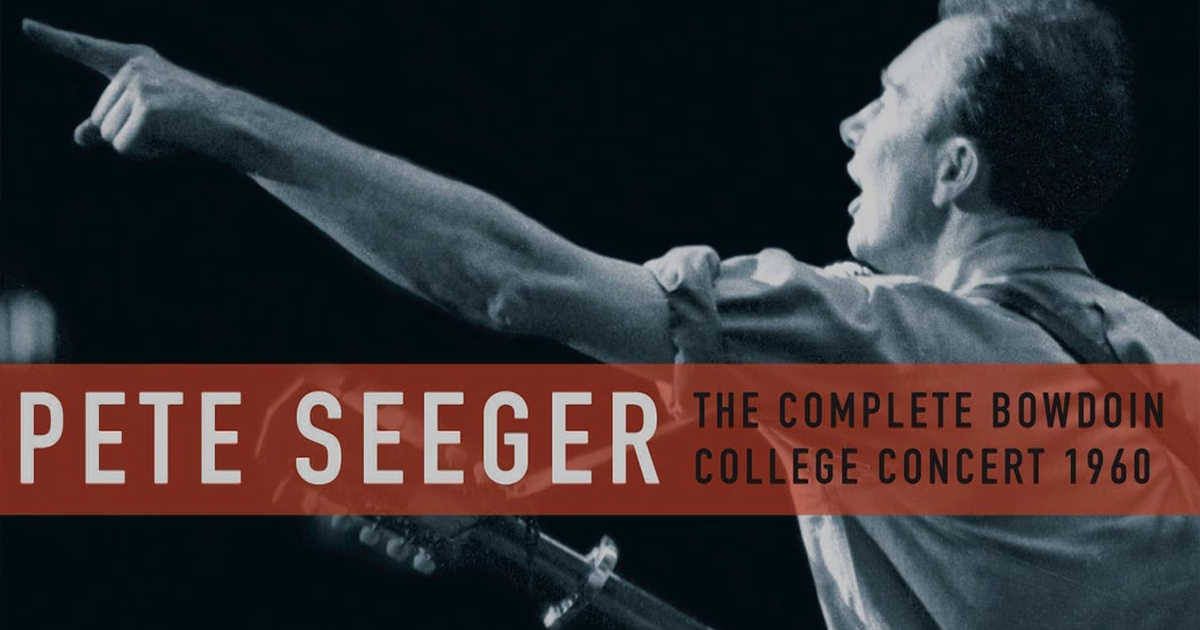

As part of a campaign to arrange shows for Pete, his manager Harold Leventhal coordinated what he called “Pete Seeger Community Concerts.” These were intended to “present Pete to an audience outside the confines of the metropolitan area of New York under the auspices of various community groups" (flyer, Ralph Rinzler Folklife Archives and Collections). Seeger played dozens and dozens of college “gigs,” which he later noted as “some of [his] most important work” (Pete Seeger: The Power of Song). Without much notice, he would arrive in a college town, do an interview on the college station, play the show, and be gone before the anti-Seeger protesters could organize a rally against him. During 1958 and 1959, leading up to a 1960 concert at Bowdoin College in Maine, he performed in Texas, Oklahoma, Colorado, Ohio, Michigan, Pennsylvania, New York, Massachusetts, Connecticut, New Jersey, and Minnesota. In the early 1960s, Pete played concerts around the world, entertaining in many countries and learning great topical songs, which he brought back to the U.S.

In March 1961, Seeger was tried on the contempt of Congress charge, which resulted in conviction. He was subsequently sentenced to ten years in jail. Thankfully, in May 1962, the Court of Appeals decided that the indictment was faulty and threw out the case (Dunaway: 259). Now able to move freely and without the cloud of prison hanging over his head, Seeger began to increase his involvement in social activism, especially the African American civil rights movement. He marched in the South with Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., and others. He gathered at the Highlander Folk School in Tennessee, and participated in re-working the hymn “I Will Overcome” into the iconic anthem “We Shall Overcome.” He was also a strong voice against the Vietnam War, penning great anti-war songs like “Waist Deep in the Big Muddy” and “If You Love Your Uncle Sam (Bring ’Em Home).”

The fight to protect the environment also captured of his attention. Seeger heard the phrase “think globally, act locally” and it got him thinking about his own area around Beacon, New York (Pete Seeger: The Power of Song). His home was on a hill over the Hudson River, which by the mid-1960s had become a festering, polluted mess. Seeger and friends built the sloop Clearwater and sailed up and down the river, performing and raising awareness of the problem. Ultimately, the river became cleaner and cleaner and the polluters were stopped—demonstrating what Seeger’s strong-minded perseverance could accomplish.

During the latter years of his career, Pete Seeger released the occasional album and frequently performed for any group or cause that could use his help. He always valued the idea of music as a way of bringing a community together around a common cause. His favorite concert performances were those where he led and the audience did most of the singing. In January 2009, he sang “This Land is Your Land” in front of hundreds of thousands of people on the Lincoln Memorial steps during the inauguration of Barack Obama as President of the United States. A Kennedy Center honoree, Pete Seeger has been suggested as a worthy recipient of the Nobel Peace Prize. In 2014, he was nominated for a Grammy award for Best Spoken Word Album. His performances, recordings, and books, all leave seeds behind that grow with those who have experienced them.

In July 2013, his wife of almost seventy years, Toshi Ohta Seeger passed away. Their marriage was a true partnership. It was Toshi’s organizational skills in working with Pete that allowed him to accomplish as much as he did.

Just days before his passing, he participated in the yearly celebration of Martin Luther King, Jr., in Beacon, New York. Up until the very end, he was out there doing what he felt was right. His voice and presence will truly be missed.

(Portions of this text represent edited excerpts from the liner notes of Pete Seeger’s The Complete Bowdoin College Concert, 1960.)

References:

Dunaway, David King. 2008. How Can I Keep from Singing?: The Ballad of Pete Seeger. New York: Villard Books.

Pete Seeger: The Power of Song. DVD. Directed by Jim Brown. 2007. Shangri-La Entertainment.