-

UNESCO Collection Week 36: Peru and Byelorussia—Work, Life, and Celebration Songs for the New Year

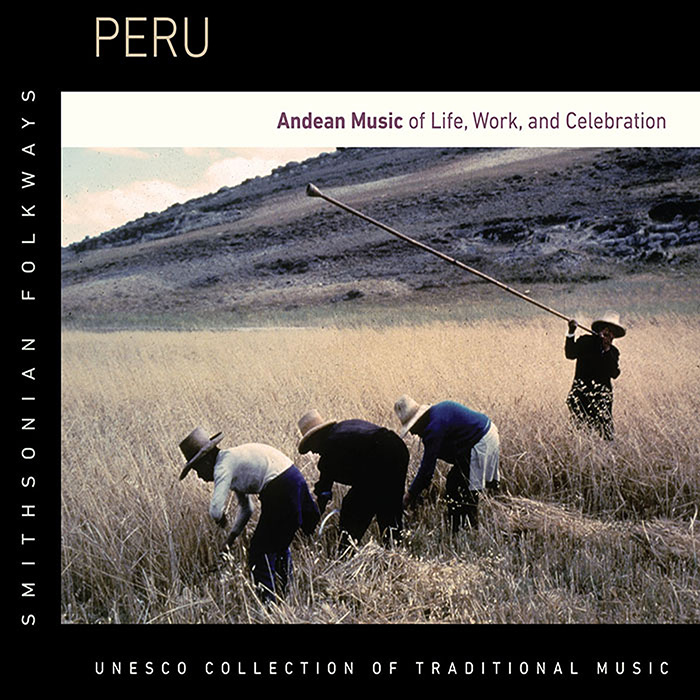

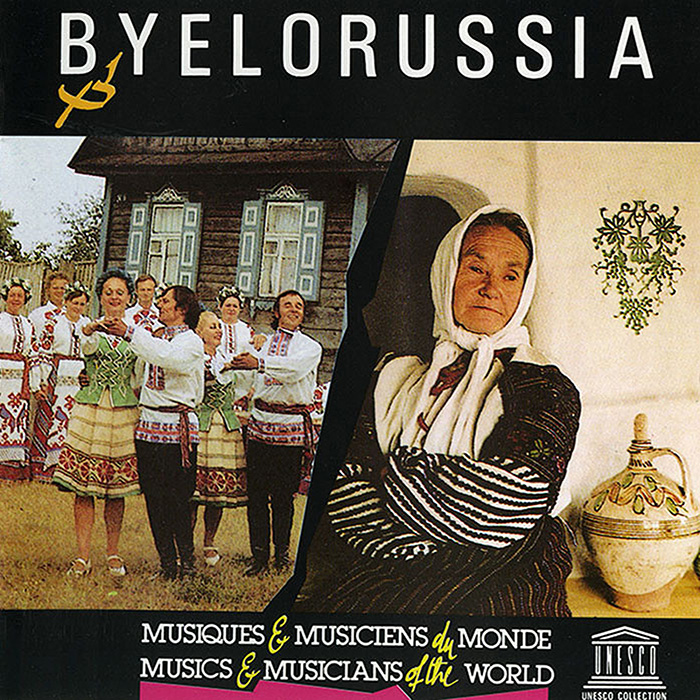

This week we celebrate the new year with the previously unreleased Peru: Andean Music of Life, Work, and Celebration with unique insight from the album’s compiler and annotator, Raul R. Romero. Alongside is the reissue of Byelorussia: Musical Folklore of the Byelorussian Polessye, featuring a glance into the musical traditions of the Belarusian Polessye by Stephanie K. Andrews. Both the albums are rare documents of the regions they represent.

GUEST BLOG

Peru: Andean Music of Life, Work, and Celebration

By Raul R. Romero

Peru: Andean Music of Life, Work, and Celebration covers a wide array of contemporary rural indigenous musical traditions from different regions of the Peruvian Andes. These have been selected from among the most outstanding historical field recordings in the sound collections of the Institute of Ethnomusicology of the Catholic University of Peru. The institute was created in 1985 thanks to the support of the Ford Foundation, and since then has accumulated one of the largest audiovisual collections of field recordings of Andean traditional music extant in the world. Many collectors, both foreign and national, who have done their field research in Peru have chosen its audiovisual archive as a permanent repository for their holdings. Before the existence of the institute, there was no secure location in Peru where the researchers could leave their recordings.

Andean musical genres of pre-Hispanic origins that had never before been included in an ethnographic record are present here. Some of the genres presented are the harawi and the wanka, monophonic songs associated with specific ceremonies and rituals like farewells and marriages, as well as with agricultural labor; the kashwa, a collective circle dance performed by young and single men and women, associated with nocturnal harvest rituals; and the haylli, a call-and-response genre rendered during communal agricultural work in the field.The other aspect that makes this anthology exceptional is that all the field recordings have been made in situ, during the actual musical performance, and in the original cultural context. This means that the musical examples of this anthology together constitute a distinctive ethnographic document of crucial moments in the lives of the people that gave rise to these musical expressions.

For a better listening experience this anthology has been divided into five sections. The first is Music and the Vital Cycle, which includes courting, marriage, and funeral music. Especially impressive are the harawi sung during marriage (track 3), and the child burial. The harawi is an a cappella style of group singing that is performed only by women, and is substantially divergent from classical Western singing styles, its main features being the extremely high-pitched vocals and an intensive use of glissandos and exclamations. In the child burial (track 5) the music is lively instead of tragic, because in the Andean world, it is believed that the child will go to heaven without sin. The song is accompanied by the ubiquitous charango (small Andean guitar).

The second section is called Music and Labor, and includes activities such as agricultural communal work, the cleaning of irrigation channels, and the construction of communal or private buildings. In the Andes, these activities are carried out with the cooperation of the whole community, an occasion to celebrate and perform music. Pay special attention to the minga tune (track 10), which comes from a pre-Hispanic tradition. In Cajamarca, where this example was recorded, the minga (communal work) with musical accompaniment had almost disappeared when this recording was made. This example is played on the clarín, a five-foot-long transverse trumpet made of cane. The waylli (track 16) is a derivative term from haylli, the pre-Hispanic musical genre that was mentioned by the early Spanish chroniclers. As it was described by them, this example expresses the festive, joyous and triumphal character of this strictly vocal genre.

The third section, Music and Dances, is of utmost importance because of the dance-dramas that accompany festivals and rituals. The music for dance-dramas follows the structure of the dance-dramas themselves, thus consisting of a multi-sectional form of two or more parts, each with different tempos and styles. In the Choqela dance (track 29) the music is played by a group of large quenas (end-notched flutes locally called choqellas) that accompany a female choir. The Scissors Dance (track 30) is a dance of competition, accompanied by a harp and a violin, and consists of a succession of choreographic sequences in which the dancers challenge one another while playing complex rhythmic figures with the scissors they hold in their hands.

The section called Carnival Music is devoted to one of the more ubiquitous celebrations in the Andes since the European conquest. One of the examples is the novillada or steer dance (track 31), accompanied by six-holed pinquillos (small vertical flutes) and drums, while others blow their pututos made of cattle horn or a conch shell that emits a lower sound.

Finally, in the section on Religious and Christmas songs, we find rare examples (track 36) like a religious hymn that the awkis (Andean priests) sing to the wamani (Andean deity) in the festival of yarqa aspiy, or the ritual cleaning of irrigation channels.

As an anthology that intends to introduce the listener to the impressive diversity of Andean music–manifested through its multiple forms, styles and musical genres and instruments, coming from different cultural areas in the Peru—this record is one of a kind. It includes samples from the historical collections of the renowned Peruvian ethnologist and author José María Arguedas (1911-1969), and of the foremost Peruvian ethnomusicologists Josafat Roel (1921-1987), as well as a recent generation of distinguished scholars in the field of Andean studies. In sum, this anthology features 40 musical examples of the best Andean field recordings of fifteen researchers. It is a rare treat that no one interested in Andean music and culture should miss.

GUEST BLOG

Byelorussia: Musical Folklore of the Byelorussian Polessye

By Stephanie K. Andrews

My interest in this album was aroused by the description of the Polessye region as "the land of legends, fairytales and songs.” Growing up with the tales of the Brothers Grimm, I’ve always had a fondness for fairytales, and was curious to see how the dark forests of Germany contrasted with Polessye’s vast meadows. Polessye is a geographical area which makes up modern-day southern Belarus and northern Ukraine, and is notable for having been greatly impacted by the 1986 Chernobyl nuclear disaster. Its music has only become the subject of widespread historical and musicological interest in the past few decades.1 Much of its music was inspired by the country's landscape—vast swampland, endless meadows, and heavily wooded areas. The earlier of two music traditions, dating as far back as the 6th century AD, relies heavily on the seasonal cycle, reflected in the order of the recordings that start with winter and end with the fall harvest. Also important was the practice of singing in the open air, which allowed the songs to carry over a large area. Stylistically, these songs feature a cappella singing, heterophonic chanting (combining several variations of the same melody), and frequent use of a drone in the bass voice. Most of the songs associated with pagan rituals have disappeared; the ones recorded here could be considered the last echoes of a long history.A second musical tradition arose between the 14th and 18th centuries during a time of frequent uprisings among peasants, and features a vastly different style and subject matter. Rather than focusing on the seasonal cycle, these songs are much more lyrical and poetic, centering on topics such as tributes to fallen soldiers, love, and comedy. This style features polyphony, with a chorus singing the melody and a high-pitched soloist singing counterpoint.

On first listen, the song in this collection that immediately stood out to me was “22. Poetic Song” (track 11), featuring the style of the later tradition with polyphony and a soloist. The subject of the song, to me, is even more compelling: it is the legend of a nightingale which cannot survive in captivity, despite the beauty of its cage. In my opinion, this story best summarizes the violent nature of this region, which has lost much of its culture amidst the turbulence of war and disaster.

AudioAccording to the liner notes written by Z. Mojeiko and I. Nazina, the traditional music of Polessye was only discovered by researchers several years before this 1981 recording. After the Chernobyl disaster in 1986, however, many residents of this region were evacuated due to proximity to the power plant. Much of Polessye is still deemed uninhabitable, despite nearly thirty years having passed since the disaster. I was able to uncover very little in my attempts to better understand this music and the region it represents, although the UNESCO album Ukraine: Traditional Music does offer a few more examples from this region on tracks 3, 4, and 15. For now, this recording gives us a glimpse into an area that seems as mysterious as the “legends and fairytales” for which it is known.

Stephanie K. Andrews

Intern, Smithsonian Folkways Recordings

1 Z. Mojeiko and I. Nazina, liner notes to Byelorussia: Musical Folklore of the Byelorussian Polessye, UNESCO Collection of Traditional Music, 1981, compact disc.

UNESCO Collection Week 36: Peru and Byelorussia—Work, Life, and Celebration Songs for the New Year | Smithsonian Folkways Recordings