-

UNESCO Collection Week 34: Balinese Court Music

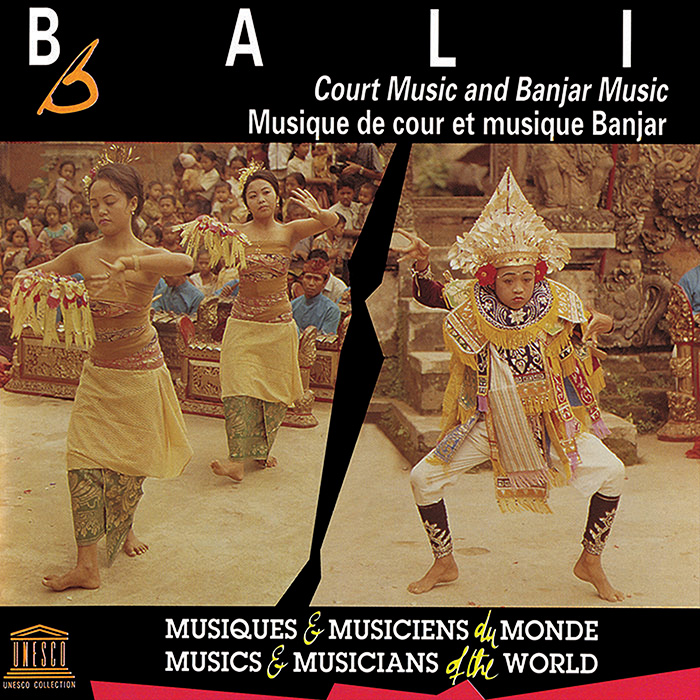

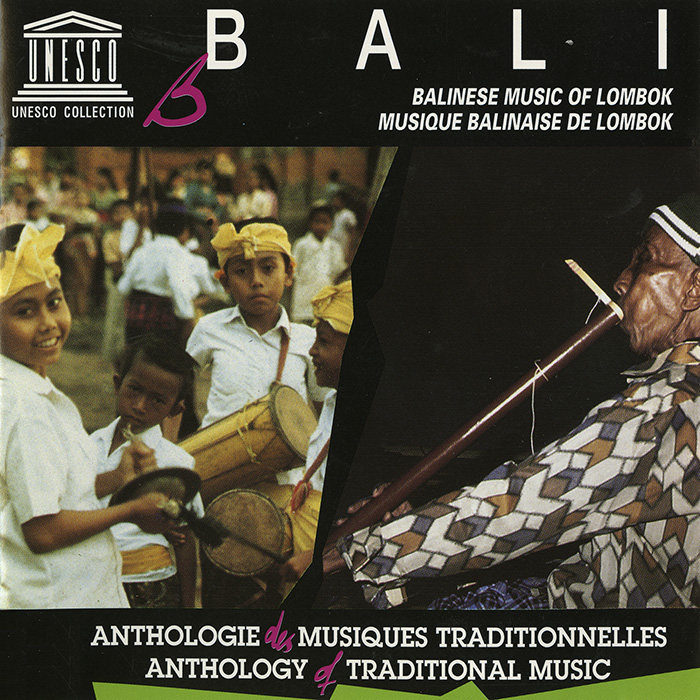

This week’s UNESCO releases coincide with the major Balinese Hindu holiday Galungan on December 16th. This holiday celebrates the victory of dharma over adharma, as well as the time when the spirits of ancestors descend from heaven to visit their homes. Bali: Court Music and Banjar Music and Bali: Balinese Music of Lombok, recorded more than twenty years apart, respectively represent the Balinese gamelan repertoire and music of the diaspora.

GUEST BLOG

By David Harnish

The scintillating sounds of Balinese music are captured on two recordings in the UNESCO collection: Bali: Court Music and Banjar Music and Bali: Balinese Music of Lombok. Jacques Brunet recorded the former in 1971; I recorded the latter, released in 1997. Despite the fact that both albums feature sounds from Bali, the music sharply contrasts in several ways. First, my recording presented the diverse ritual music of the diasporic Balinese on the island of Lombok, whereas Brunet’s featured exclusively the 20th century gamelan gong kebyar repertoire.

Additionally, there is a stretch of 26 years between releases. When Brunet was active in the 1960s and1970s, “Bali” was an icon of the Asian exotic with dynamic and dazzling performing arts and attracted a growing international audience seeking to experience the romanticized “other.” This sentiment had died down by the 1990s, particularly within ethnomusicology, and I sought to distinguish religious music “traditions” of the Balinese living in Lombok without considering aesthetics.

Brunet recorded two major sekaa (clubs) dedicated to gong kebyar of the 20th century, one emerging from the puri (palace) of Peliatan and the other from the banjar (hamlet) of Belaluan Sadmerta in Denpasar–thus the “Court” and “Banjar” of the album title. The gamelan gong kebyar, featuring faster and changing tempi and a wide variety of innovative dynamic interlocking parts (kotekan), emerged around 1915 in north Bali and soon spread throughout the island, with Peliatan and Belaluan Sadmerta becoming centers.AudioThe court music of the title is a little misleading because gong kebyar music does not function within the courts; the sekaa of Peliatan, the famous Gunung Sari, was simply co-organized and directed by a prince. The album features five pieces from Peliatan and two from Belaluan Sadmerta. The compositions by Peliatan are the same as those the featured sekaa still performs today. Though well recorded, there are two “mistakes” in “Baris” due to the musicians recording this dance piece without following a dancer. Of the two sekaa, only Belaluan Sadmerta performs a piece that functioned in the courts: “Legong Kraton.” Though the distinction between “Court” and “Banjar” is entirely arbitrary, this release nicely encapsulates the core gamelan gong kebyar identity of the 1950s to 1970s, and visitors today are still likely to hear most of the recorded pieces at tourist performances.

I wanted Bali: Balinese Music of Lombok to represent the diaspora and its unique history on the neighboring Islamic island of Lombok. Occupied by Balinese rajas from the 17th through the 19th century, local Balinese reimagined and adapted “Bali” and Balinese music as religious minorities in Lombok. In the process, they sought to preserve styles (that eventually changed in Bali) and their Hindu religious identity while also assimilating into the new environment of the Muslim Sasak majority. This resulted in appropriation and hybrid music formations.Since the main performance contexts are religious rituals, the recording features pieces by the well-preserved ceremonial gamelan gongs kuna, angklung, and baleganjur, along with the double-reed preret–which has been adapted to contact local deities of Lombok at Balinese temple festivals. Most pieces are “older”: relatively static and without the dynamism of those on Brunet’s album.

Another style featured is wayang Sasak—the Sasak shadow puppet play tradition that highlights Amir Hamza, the uncle of Prophet Muhammad who clears the path for the coming of Islam. Hindu Balinese have sometimes been leaders in presenting these Islamic tales in Lombok. The recording concludes with a performance of “cakapung,” a “vocal” gamelan with bowed lute and flute and a variant on Bali of the Lombok cepung, which was co-created by Balinese and Sasak in the 19th century. Since the release of this album in 1997, the Balinese cultural expressions in Lombok have evolved to be more like those in Bali as modern technology and Hindu reform movements have encouraged local Balinese to closely emulate the predominant culture.

David Harnish is Professor and Chair of the Music Department at the University of San Diego. Author of Bridges to the Ancestors: Music, Myth and Cultural Politics at an Indonesian Festival (University of Hawaii Press, 2006) and co-author/editor of Divine Inspirations: Music and Islam in Indonesia (Oxford University Press, 2011) and Between Harmony and Discrimination: Negotiating Interreligious Relationships in Bali and Lombok (Brill Press, 2014), he is a double Fulbright and National Foundation Scholar and has consulted for the BBC, National Geographic, MTV-Fulbright Awards, and the Smithsonian Institute. As a performer, he has recorded Indonesian, jazz, Indian and Tejano musics with five different labels. He co-directs Gamelan Gunung Mas at USD and serves as USD Academic Liaison for the Kyoto Prize Symposium.

UNESCO Collection Week 34: Balinese Court Music | Smithsonian Folkways Recordings