-

UNESCO Collection Week 3: Strings of Ireland and Norway

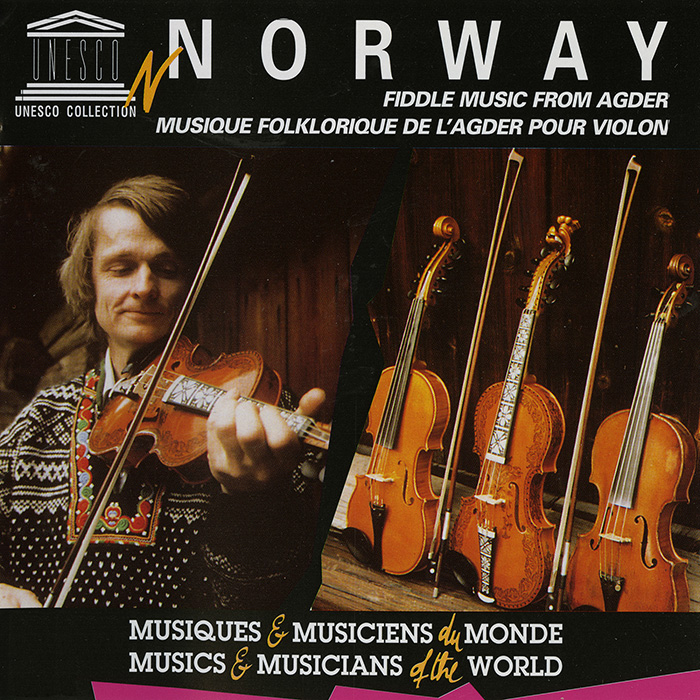

Week Three in the UNESCO Collection of Traditional Music release takes us to Europe, with a comparison of Norwegian hardingfele fiddle tunes to Irish seisiúin music.

GUEST BLOG

by Ian Martyn

The Hardanger fiddle, or hardingfele in Norwegian, is an ornately decorated fiddle with eight or nine strings, four of which are tuned and played as on a standard violin. The other four or five act as sympathetic strings, sounding purely through the influence of the main four strings without the touch of the human player.

Listening to Norway: Fiddle and Hardanger Fiddle brings back memories of my time in the fjords of Norway, the echo-like sounds of the sympathetic strings evoking images of tall mountains surrounding the glistening, narrow passage of water. These sympathetic strings work in tandem with a preference for double-stops which appear in nearly every tune for the hardingfele. The soloistic style of the instrument, accompanied only by the stomping of dancing feet where appropriate, evokes the vastness of Norway itself, apparent when traversing the great length of the country. Vidar Lande’s performance on tracks such as the opening “Førespel” exemplify this vastness, showing off the ringing of the sympathetic strings with slow, virtuosic playing.AudioOn the other hand, foot taps on “Reinlender frå Åseral” show off the hardingfele’s ability to provide music for dancing, the infectious rhythms accentuated by double stops, heightening the sense that a group of instruments is playing rather than just one.

AudioIreland represents a mostly soloistic approach to Irish music, although the beginning starts off with some live recordings of tunes to accompany dancing. A wide range of styles are represented here, and the inclusion of an ample amount of sean-nós (old-style Irish solo singing) in the Irish language is a welcome find in light of recent Irish language revival successes. For an example of sean-nós, listen to Nioclas Toibin's “Ar Bhruach na Laoi san Oíche do Casadh mé.” The progression of the selections makes the listener feel as though he or she is sitting in a room full of musicians, with each musician taking his or her turn to show off a different instrumental tune or song.The range of music represented on Ireland reminds me of the time that I spent playing in the pub seisiúin (Irish music sessions) on the western coast of Ireland. The focus of the seisiún is communal playing rather than solo, and this feeling is exemplified by the event’s social aspects. As Dorothea E. Hast and Stanley Scott observe in the book Music in Ireland, “their playing is neither a performance in the conventional sense nor background music. Instead, they are a complete unit within themselves—playing for each other and immensely enjoying another’s company” (Hast and Scott, 5).

Making a direct comparison of these two compilations is perhaps most easily done by examining both musical traditions in relation to dance. The biggest revelation is that the hardingfele itself acts as multiple musical instruments. First, listen to the tune set “Cherish the Ladies/Tobin's Favourite/Jerry's Beaver Hat,” performed by Carcur Mummers’ Group on the Ireland compilation. Notice how the accordion plays both the melody and some accompanying chords while dancing feet tap out a rhythm. This style can most closely be compared to the hardingfele as used in dancing music, where its sympathetic strings work with a melody-and-drone style of double-stop playing to drive the stomping of the dancers’ feet.

In a very similar way, this same double-stop technique echoes the Uilleann pipes in Irish music. Often used to play slow airs, a style of lamenting, free-meter tune, these pipes contain a set of regulators, drone pipes with valves which change the pitch of the drones. This movable drone functions in the same way as the technique of striking two notes at the same time on the hardingfele. One can hear this style exemplified in “An Chúileann” as played by Johnny Doran on the Ireland compilation. In both cases, these drones help to settle the melody, even in the absence of aspects typically found in music such as a steady beat. As Sean Williams, an expert on Irish music and sean-nós, states in her book Focus: Irish Traditional Music, “the drones of the pipes, which establish a continuous ‘floor’ against which the melody is played, reinforce the notion of a tonic of ‘home’ to which the melody returns” (Williams, 11).

AudioAlthough clear differences exist between these two musical traditions, one cannot help but notice the connections they share. With Irish and Scandinavian traditions interacting closely, both in geographical and cultural contexts, these similarities demonstrate how musical styles can travel from one culture to the next.

Ian Martyn, M.A.

University of California – Davis, Ethnomusicology

Independent Musician and DJHast, Dorothea E. and Stanley Scott. Music in Ireland. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004.

Williams, Sean. Focus: Irish Traditional Music. New York, NY: Routledge, 2010.UNESCO Collection Week 3: Strings of Ireland and Norway | Smithsonian Folkways Recordings