-

UNESCO Collection Week 2: Twenty Generations of Indian Dhrupad

We are now in full swing with the release of the UNESCO Collection of Traditional Music via digital download, streaming services, and on-demand physical CDs. Two albums will be released each week, complemented by a guest blog post, until all 127 albums—including 12 that were previously unreleased—become available.

GUEST BLOG

by Anne-Marie Gilliland

What is dhrupad?

A good question.

Before researching for the UNESCO Collection of Traditional Music, I had never heard of dhrupad, considered the oldest form of Indian vocal music. It has been exciting for me to work with these world heritage albums, and I now have a broader appreciation and knowledge of diverse cultures and can share what I’ve learned with others. It may not be a passport stamp, but my ears have heard sounds and songs that in some cases were endangered of not being heard by future generations.

Part of what makes these two albums so special is the concept of heritage, a tradition of passing the music down through the generations. It has been a moving experience to learn about dhrupad. By listening, I have become part of the tradition in a small but not insignificant way.

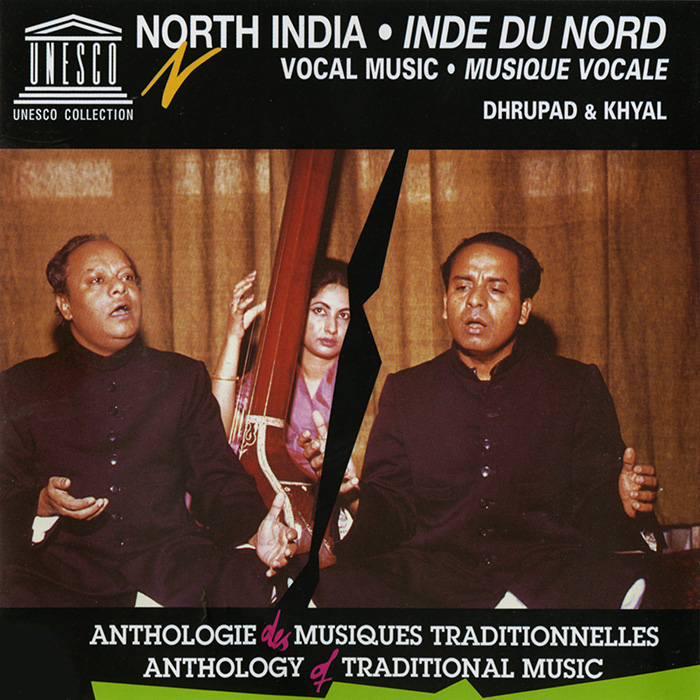

North India: Vocal Music: Dhrupad and Khyal, recorded in 1965, includes two tracks, the first of which is a dhrupad. Dhrupad is remarkable in that it can be traced for twenty generations through a single familial lineage. This album captures two brothers of the Dagar family: Moinuddin and Aminuddin. They toured Europe in the 1960s and helped bring dhrupad back into the cultural forefront.AudioMuch of this piece, “Alap and Dhrupad,” consists of the vocals passing between the brothers. In this clip, however, you can here them singing in tandem. This reflects the very nature of dhrupad music. It is very much an oral tradition being passed down through the generations: they are part of the 19th generation in this gharana1. As Mani Kaul, an Indian filmmaker, said in an interview:

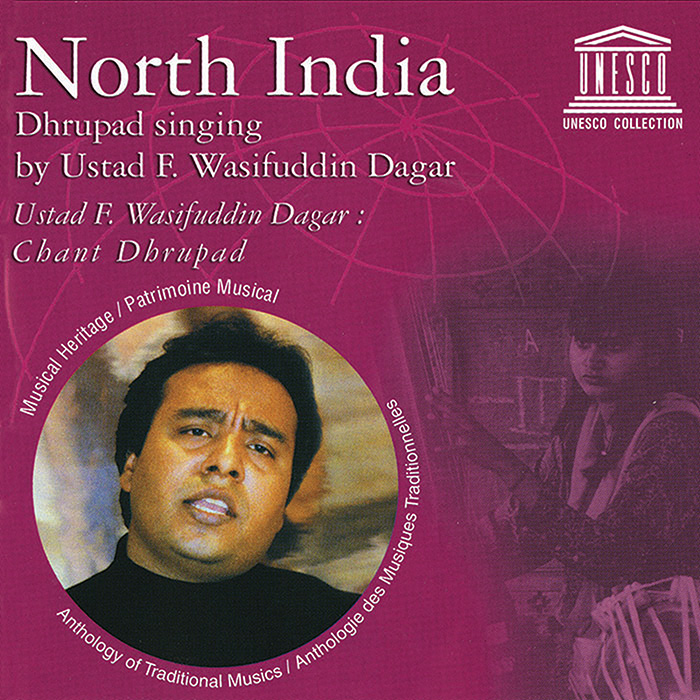

“In this music, individual musicians must express their own individual selves as they are. That's the secret of this tradition: if you wrote down phrases and forced people to learn only a certain way of playing, the tradition would die.”2Upon Moinuddin’s death in 1966, the younger pair of Dagar brothers, Ustad Nasir Zahiruddin and Ustad Nasir Faiyazuddin, took up the mantle of sharing dhrupad music. While the UNESCO collection does not include a recording of the younger Dagar brothers, Faiyazaddin’s son, Wasifuddin (Wasif), was recorded as he continues the family tradition.

After performing with both his father and uncle Zahiruddin until each died, Wasif performed dhrupad alone. Wasif’s solo dhrupads can be heard on North India: Dhrupad Singing by Ustad F. Wasifuddin Dagar.In this style, a pakhavaj (drum) and tanpura (lute) accompany the singers. The singer sits cross-legged, center-stage, with the musicians in the background, usually to the left and right.

Both of these dhrupads begin with a long introduction known as an alap. An alap lacks the drumbeat of the dhrupad proper and the vocalization is wordless. It is meant to set the mood for the dhrupad to come. Like all Indian classical music, these dhrupads have specific ragas, which can indicate what time of day a song should be played. The dhrupad on the elder Dagar brothers’ album is intended for nightfall, while the first dhrupad on Wasif’s album is intended for midnight.

It’s inspiring to know that there is a familial musical tradition that has continued for twenty generations and is also available to the world.

For further reading, visit:

“Dagarwani” by Uday Bhawalkar

Dagarvani.orgAnne-Marie H. Gilliland, M.A.

Intern, Smithsonian Folkways

Past Adjunct Professor of English, Anne Arundel Community College

1 “hereditary musician families known as gharanas, which operate as semi-professional guilds in which successful maestros handed down musical learning to their sons, nephews, grandsons and grandnephews and on occasion to a talented male apprentice outside of the family.” Two Men and Music: Nationalism In the Making of an Indian Classical Tradition Janaki Bakhle

2 “A Critical Cinema 3: Interviews with Independent Filmmakers,” Scott MacDonald, 1998, pg 172-173.

UNESCO Collection Week 2: Twenty Generations of Indian Dhrupad | Smithsonian Folkways Recordings