-

UNESCO Collection Week 16: Lesser-known Music from North India and Pakistan

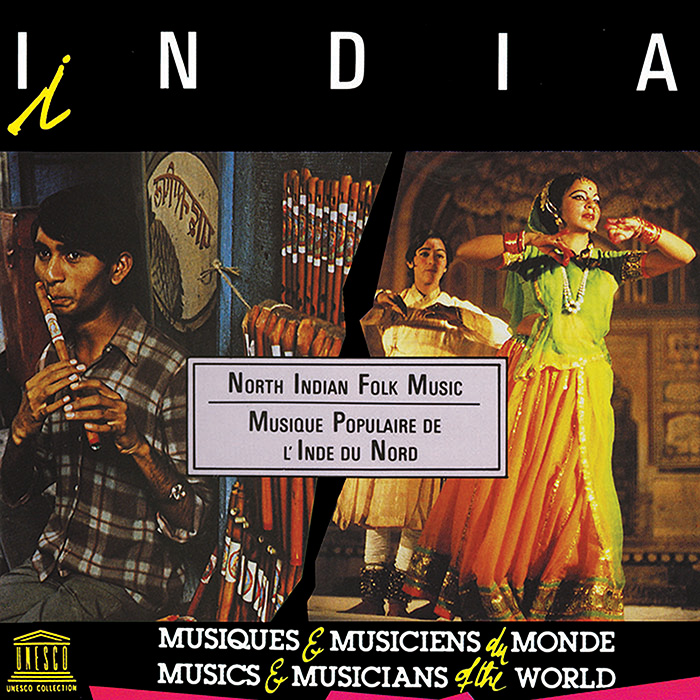

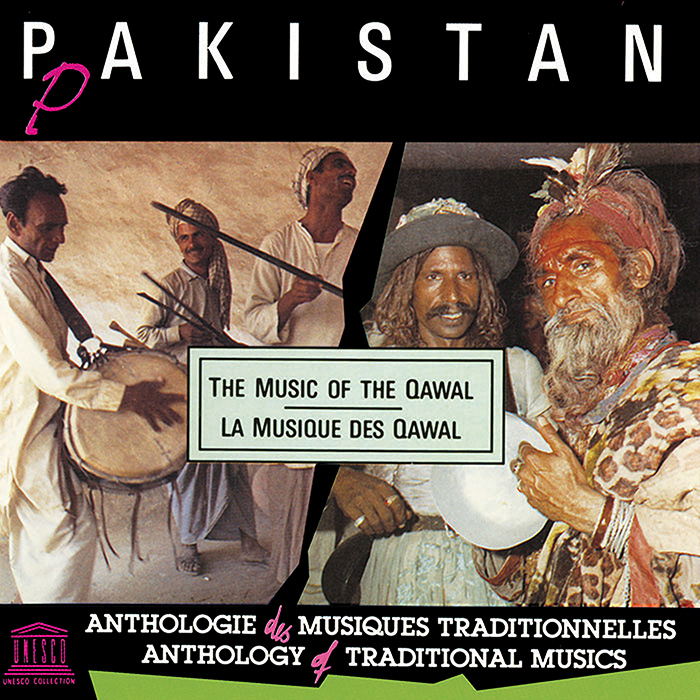

Week 16 of the UNESCO Collection of Traditional Music spotlights Pakistan and India on the eve of their respective Independence Day celebrations on August 14 and 15 with the albums Pakistan: The Music of the Qawal and India: North Indian Folk Music.

GUEST BLOG

by Shalini Ayyagari

Both of these albums are outliers to the Hindustani classical music canon. Although the musics on close listening and analysis are very different from one another, both have suffered marginalization in and out of South Asia in comparison to better-known forms. While these recordings were made in the 1970s, contemporary listeners come to each of them with new assumptions and references on music. I therefore invite you to critically listen to these two albums, keeping in mind the assumptions and popular perceptions of the styles of music represented here.

When I first heard North Indian Folk Music, I couldn’t help but notice the eclectic selection of songs. We move from “Kajri,” sung during the monsoon season in villages near Banaras and featuring a male singer, chorus, and percussion, to a “Bhajana,” or Hindu religious song, sung by an Indian wandering sadhu (holy man) accompanying himself on tintara, a stringed drone-producing instrument.AudioWhat seems to link these songs curatorially is their functionality. Liner notes author Manfred M. Junius writes, “Music is woven into the lives of the Indian people of every province... and the folk music reflects the individual characteristics of these cultures as well as their mixtures.” It is often this functionality that causes such music’s placement into the category of “folk.” Yet the listener could ask: what music is not functional? Hindustani classical music can be heard as also performing a social function. Is it the function of the music that determines whether music is “folk” versus “classical”?

The persistent dichotomization of “classical” versus “folk” is problematic and false. Scholars have demonstrated that much classical music derives its melodies, rhythms, subject matter, and theory from folk music, just as those types of music classified as folk also derive source materials from classical music. In South Asian ethnomusicology, the continued dominance of Hindustani classical music over popular and folk parallels the hierarchy of social values in South Asia in general, laden with colonial dynamics, subaltern discourses, and regional/religious/class differences.

AudioFor example, consider the fifth track on the album, “Dhun on the shahnai,” performed by shahnai (Indian oboe) musician Hiralal. Junius describes the nature of Hiralal’s playing as retaining a “certain rustic element”; instead, I hear nuanced musical articulation, attention to theory and raga, and refined musicality. Hiralal draws on Hindustani classical theory in his exposition of raga, use of drone, phrasing and development, repetition, and nuanced rhythms and tihais of the accompanying duggi (small pair of kettle drums).

Qawwali, the music featured on Pakistan: The Music of the Qawal, often suffers the same marginalization in South Asian ethnomusicology. Considered to be “folk” music from Pakistan, qawwali is a form of devotional music popular in the northern regions of contemporary India and Pakistan. It is steeped in Islamic religious and Sufi mystical traditions, and the lyrics convey the message of Allah.The qawwali featured on this album is performed by the Sabri Brothers, an internationally known family of qawwali singers. Qawwali artists, like those from the Hindustani classical music tradition, often claim a musical lineage stretching back to the legendary Mian Tansen, the famed singer of the Mughal emperor Akbar’s court.

The liner notes by the French musicologist and Indologist Alain Daniélou provide helpful descriptions of the history and subject matter of qawwali as well as detailed translations of the songs from Urdu into English and French. Yet qawwali’s marginalization comes through in the choice of photographs of non-qawwali performers for the liner notes and the lack of theoretical musical discussion to describe the nuanced musical form, role of the instruments, and lifelong training of the artists.

The second track, “Nât Sharîf,” describes the all-consuming love of the singer for the prophet Mohammad and the lifelong search for the Divine on the path of life. This particular track features virtuosic vocal solos interspersed with refrains of a repeated melody and line of text. The professionalism and musical training of these talented artists is unmistakable.

AudioI hope that current and future attention to regional musical traditions such as those featured on these two albums will help counteract their marginalization as secondary to Hindustani classical music. These collections mark a step in the right direction.

Shalini Ayyagari is an ethnomusicologist and Assistant Professor of Music at American University in Washington, D.C.

UNESCO Collection Week 16: Lesser-known Music from North India and Pakistan | Smithsonian Folkways Recordings