The Academy of Maqâm

For centuries, the elegant classical music tradition known as maqâm has captivated listeners across a wide swath of the Muslim world. From North Africa to Western China, varieties of this tradition convey a diverse wealth of musical expression. The melodic and rhythmic nuances of maqâm have long permeated the music of Central Asia, a region that comprises a rich heritage of cultures and landscapes. From the great and bustling cities in Iran to the south to the nomadic lifestyles of peoples in the wilds of Turan, the Inner-Asian steppe to the north, the blending of these cultures and their folk traditions has given rise to distinctive musical forms that have been preserved and reinterpreted throughout centuries of political upheaval. Today, traditions of maqâm in Central Asia continue to thrive in large part through the dedication of musicians, governments, and others who acknowledge their important place in the region's cultural heritage.

Nestled among the majestic Pamir Mountains in Dushanbe, Tajikistan, the Academy of Maqâm was founded, with support from the Aga Khan Music Initiative in Central Asia, by Abdul Abdurashidov, a Tajik musician with a passionate commitment to the preservation of the Central Asian sub-genre of Shashmaqam. Literally referring to "six maqâms," the Shashmaqam canon comprises six pieces, each based on a different melodic mode of traditional maqâm music. Typically performed as cycles or suites, each Shashmaqam combines the emotional quality of its particular melodic mode with the lilting, rhythmic ambience of antique Persian poetry—usually the words of longing and desire of the great bards of Sufism, the mystical dimension of Islam.

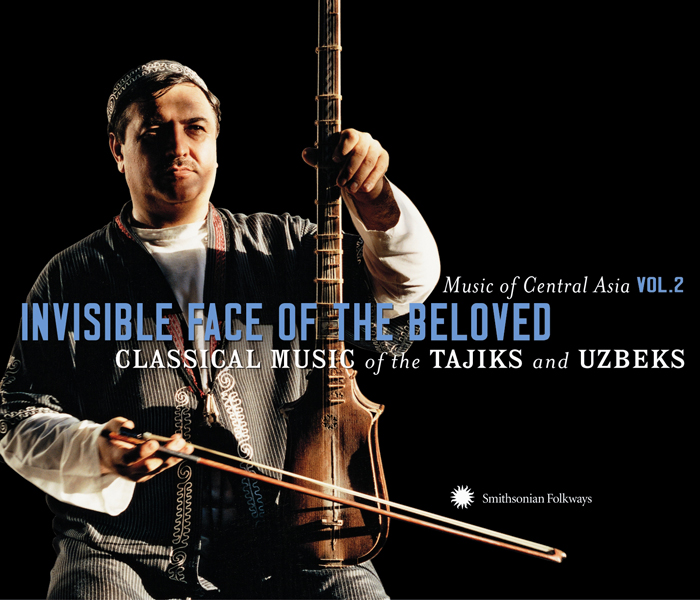

The suite Abdurashidov performs with his students on Smithsonian Folkways' 2006 release Music of Central Asia vol. 2: Invisible Face of the Beloved: Classical Music of the Tajiks and Uzbeks is the Maqâm-I Râst, which utilizes the râst mode as its primary melodic foundation. Though the performance recreates the wholeness and majesty of the Shashmaqam suite, it is executed with deceptive deftness and confidence.

Abdurashidov's persistent commitment to Shashmaqam has been a major factor in the music's resurgence, and his unique teaching style, which values tradition over more modern musical education, has been an indispensable part of his success. As Abdurashidov explains, the Academy of Maqâm did not simply arise out of prior institutions. Rather, much of the inspiration for establishing the academy grew out of a desire to respond to the changes in methods of musical transmission and learning brought about by the cultural authorities of the Soviet Union. He describes how, beginning in the late 1920s, students were taught that the proper way to learn and study music was through written notation, and that the direct tutelage of a master was therefore irrelevant, unnecessary, and "backward." According to Abdurashidov, this Soviet intervention and "modernization" of musical pedagogy stood in the way of proper transmission of classical Central Asian music, which had relied primarily on a master-disciple system. As a result, Abdurashidov instituted an environment at the Academy of Maqâm in which students not only study musical techniques directly from master musicians but also take lessons in poetry, metaphysics, ethics, and other subjects. The Academy therefore offers both a musical and a cultural education that emphasizes the importance of music as one cornerstone of a greater Central Asian heritage.

Although the modes, instruments, lyrics, and techniques utilized in today's Shashmaqam resemble those used for centuries, much of the repertoire continues to develop and change. Shashmaqam itself is a unification of a number of musical pieces into a whole greater than its parts, many of which are left up to the discretion of the performers. For instance, the introduction heard on the Maqâm-I Râst suite on Invisible Face of the Beloved is a solo played by Abdurashidov on the sato (a traditional Central Asian long-necked lute), which he substituted for a much longer instrumental section. Though he omits this section in the interest of brevity, Abdurashidov also includes a solo for the purpose of "tuning" the musicians, to "set a mood and create an ambience for what will follow. " Similarly, the taronas—shorter pieces used as segues between sections of the suite with different modal and rhythmic qualities—are not necessarily rigid, and may be substituted for one another to produce the intended result. Shashmaqam music is thus defined both by an internal flexibility and an overarching commitment to the unity of a particular suite. Another unique element central to Abdurashidov's approach to Shashmaqam arose out of his individual experience of the music. He notes that the commonplace modern performance of maqâm music as individual and discrete pieces, separated from the context of the cyclical suite, fails to achieve the unity and ultimate experience that the Shashmaqam engenders when it is performed as a whole. Abdurashidov has found that performing and listening to Shashmaqam pieces when they are integrated with one another into a larger whole "can lead to an entirely different understanding and experience of the music—to a kind of self-purification." He therefore performs and teaches the music according to this mindset, reintroducing an element from the beginning of a suite during the final section in order to remind the listener of the connectedness of the entire piece.

Through their holistic and decidedly traditional approach to the study and performance of Shashmaqam, Abdul Abdurashidov and the students of the Academy of Maqâm have done much to reanimate this important tradition. The beauty and depth of their presentation of the music speaks to its profound power and majesty. As the Sufi mystics, whose words they sing, express an intense and undying longing to see the allegorical "face of the Beloved," so too do these musicians' devotion and emotive sacrifice resound with every note of their moving songs. Their devotion and talent has been recognized around the world. In 2006 Invisible Face of the Beloved was honored with a GRAMMY nomination for Best Traditional World Album.